The Page Street workshop has seen a lot of stuff.

Page Street

It was April 2006 when Jay and I moved onto Page Street. It was my 4th workshop since I’d begun building bicycle frames, and I was still relatively new at it, one of the youngsters. Of the shops that came before, this one was far and away the best space I’d worked in. I was cheap because I was poor, always after the lowest possible rent. This meant dealing with leaky roofs, killer drafts, dim lighting, too-friendly rodents, unstable time-frames. I avoided leases because I didn’t want to be tied down. I thought of myself as a traveler and didn’t want to impinge on the lifestyle, my freedom to move. And yet, I was beginning to realize that if I wanted to be in the business of building bikes I needed a stable place in which to make it happen.

Seat stays inspired by the St. Johns bridge (This photo was out the back door of our workshop. You can see the foundation for condos being poured in the foreground.)

The previous workshop Jay and I shared was a condemned warehouse in St. Johns, up in North Portland, just beside the bridge. Rent was $90/month — $45 each — and that winter was hard. The building was so full of holes I may as well have built frames out in the yard. I was tougher back then, though, or just dumber. You could say I had different priorities — I was more willing to suffer to save some cash. We were in the St. Johns shop for almost a year before the owners sold the building, and it got bulldozed to make way for condos. This was one more step in the arrival of what I call “New Portland.”

Jay found the ad for the Page Street shop on Craigslist. It wasn’t exactly paradise — like the previous place it was leaky, drafty and had no heat when we moved in. But the things it had going for it were it was spacious, centrally located, and, more than anything, it was stable. We had a lease, which meant I was committing to frame building, or at least pretending to. I still needed to figure out what my business was, exactly, and how I wanted to go about things. The Page Street shop would give me what I needed to do that. Although I had no idea I’d be here for this long.

From the beginning we called this space “the shop.” Nothing formal, no capital “s,” just a place name: I’m headed to the shop. Let’s meet at the shop. And now, over the past few weeks I’ve been saying something that feels very weird: I’m moving out of the shop.

The space is a 1200 square foot rectangle with a couple of big musty back rooms for ample storage. Jay and I split the rectangle long-ways down the middle and put up sheet plastic between the front and back storage spaces to cut down on the drafts. We tried every kind of heater until we settled on a pellet stove. We stuck the flue out a window to route the smoky exhaust outside. There were at least three offices in town that would have shit themselves and shut us down if they’d seen this. I put a platform on caster wheels to hold the stove, and like, whenever we got wind of a fire inspector coming we popped the flue out of the window, wheeled the stove into the storage room and kept a straight face until we passed inspection.

Jay and I had met while working at River City Bicycles — my last job before I started building bikes full time — and Jay had a side hustle wrenching on old Mercedes diesels. He took the half of the shop with the big roll-up door to move cars in and out, and I set up my meager tools on the other side.

The shop disguise

The business that’d been here before we arrived was a good-ol’ boy race car shop called Competition Motorsports. I never figured out what exactly they did. Sold some parts, maybe installed them, money laundering, who knows? This was Old Portland, where they did things a little bit different.

When we moved in we inherited the Competition Motorsports awning. I thought this was perfect irony — I was righteously, pretentiously, into human powered machines — not motors. And for me cycling had never been competitive. I was a commuter and into bike touring.

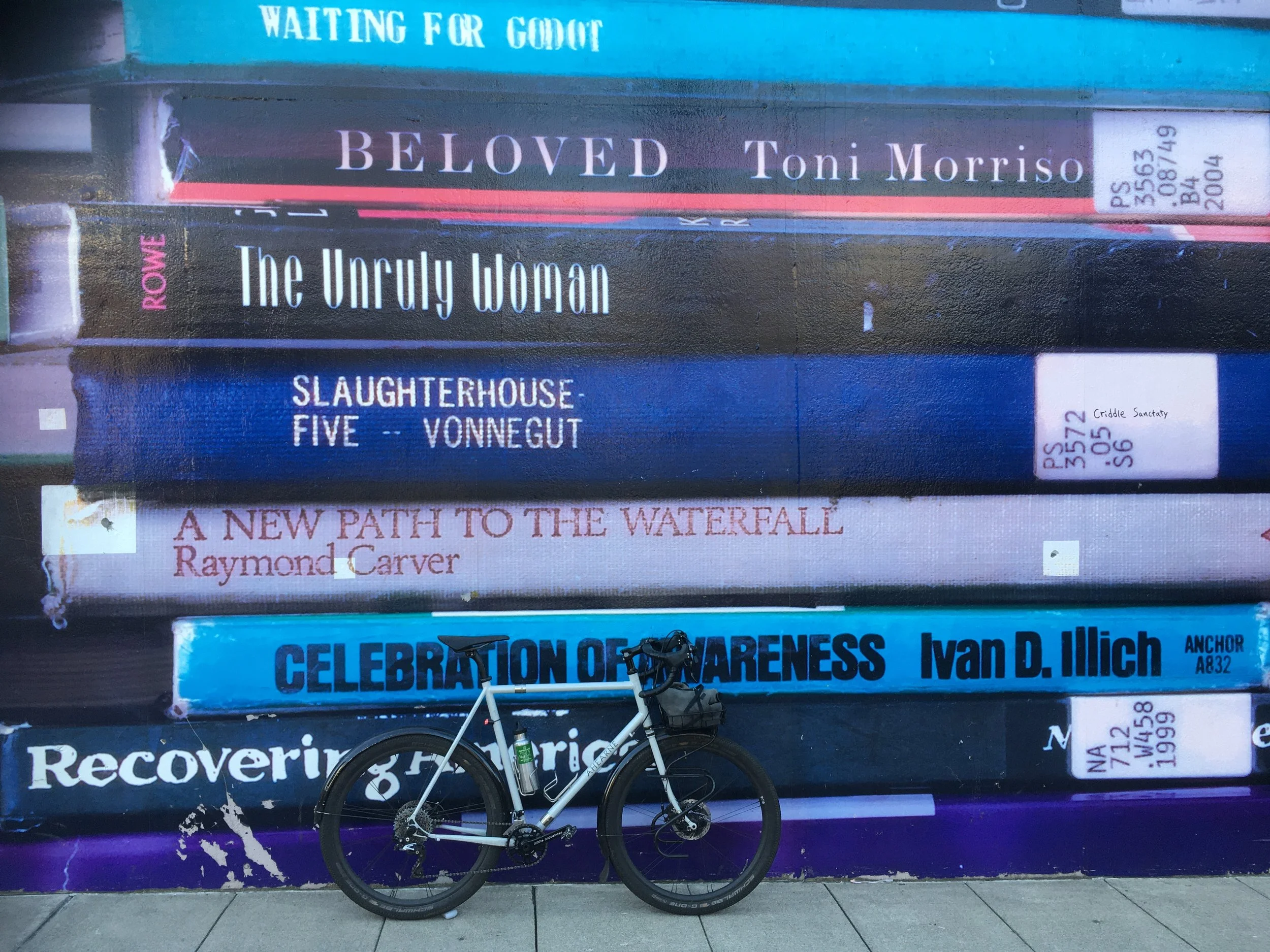

M & J and Sherman making mouths water with French fry exhaust on our way to a bike show

Jay’s cars obviously had motors, but in my book they got a pass because he converted them to run on old frier oil. A few years later, Maggie and I co-bought a car from Jay. It was a blue ’84 Mercedes wagon we lovingly called Sherman.

At this point in my life I hadn’t owned a car in over ten years. Remember, I was cheap, and I thought the cost of owning a car was ridiculous. Remember, too, I was willing to suffer inconvenience to keep cash in my wallet. Seeing things a new way was a slow evolution.

Anyway, I built Jay a bike frame as my part of the car purchase. There was something satisfying about trading a bicycle for a car.

Filling Sherman's auxiliary tank with filtered frier oil (back when I had more hair)

Maggie and I had Sherman for years. To fuel it we went around town to various restaurants, a couple of Thai places, a burger joint, collecting their used frier oil. At the shop I set up a gravity fed filtration system to clean the oil, turning it into usable fuel. It was a hacked-together system of buckets and hoses that regularly sprung leaks and we’d end up with veggie oil slicks on the shop floor. Seriously nasty stuff, it turned to a tacky sort of shellac if I didn’t get it cleaned up right away. But on the other hand nobody was killing anyone for it, and my oil slicks weren’t destroying any oceanic ecosystems, just my clothes and shoes.

Maggie and I drove that car all over the west, to go camping and to bike shows, from BC to Baja, Mexico, almost all of it fueled on veggie oil. This is a whole other story, though, for another time.

"Old" is the key word here

Symbol of the lotus flower

To move on… All these years later the awning is still up and you see it’s kind of nasty looking. Decades of wet weather, it changes colors with the seasons. The cloth absorbs pollen in the springtime that feeds lichen and moss that flourish like it’s a living organism. Most people wouldn’t consider it storefront material, but I loved it. My preference is to be in the background, and back then I didn’t mind being somewhat difficult to find. Besides, there’s a story in it — a filthy awning, a dilapidated building, the romantic vision of beauty coming out of the muck. Hence the lotus flower on my head badge (between the feet of the “A”).

Sometimes it's hard to see the human in the room

Despite having a somewhat repellant appearance we got regular visitors, people just walking in. But for the first years it wasn’t bike people who showed up. It started a few days after Jay and I got the keys, these old white men would fling open the shop door and barge in like they owned the place. They’d stop just inside, eyes squinched up and moving all around, overwhelmed with the barrage of stuff: Bike wheels hanging from hooks, benches, vices, hand tools, helter-skelter lights, machine tools, car parts, torches, pumps, partially assembled frames, art stuff and cranks and chain rings stashed floor to ceiling, all up and down the walls. If you ever visited the shop you know how much there was to see in every square inch of the place.

With the riot of visual stimulation it was sometimes hard for these old guys to locate Jay or I in the fray, but at some point they’d see one of us at work, either me standing at my vice holding a file or Jay rolling out from under a jacked-up Benz. If they registered both of us at the same time they always turned towards Jay first. Familiarity maybe — at least what he worked on was a car.

They’d tease out the question, bewildered, “Is Ron around?”

They meant Ron, the former owner of Competition Motorsports. Either Jay or I would have to break it to them.

“Ron quit the business. The race car shop closed.”

The old guy would stand there a few beats, gumming at the news, scowling like they weren’t sure if they believed us.

As it started to sink in they’d throw a thumb back over their shoulder and plead, “But the old awning’s still up.”

Like I said, this happened for years. I called them Codger Visitations. I thought about making a sandwich-board sign to set out on the sidewalk explaining things to ward them off. But I admit I kind of liked the intrusion. I could sense that this was what it looked like when a piece of history began to fade. Like I said, Competition Motorsports was a business I associated with Old Portland — the weird, one-off shops that were here in the 90s when I first arrived, most of them gone now — the UFO shop in SW Portland, the hippy kitchen shop, Magnolia, that used to be on SE 21st & Division; the Church of Elvis downtown, the Daily Grind with their amazing pies on Hawthorne, dozens of other gems that helped give Portland its unique flavor. Everything’s always changing, right? Things come and things go.

When these old guys walked in I felt like I was witnessing how a story, or a whole batch of stories, fall away, moving from the present into the past. Pieces of Old Portland fading, turning translucent as a ghost.

To a man these race car dudes were pushing eighty years old. They sported slick bomber jackets with brand patches on the sleeves, had droopy eye sacks and white wisps of hair poking out of their tall mesh ball caps. An early breed of motor head now gone quaky, liver-spotted, and a little bit frail.

All workshops have their own sense of order

I think I knew what these old guys wanted, or at least some of it. Their excuse was to buy a part or show off their car knowledge, or learn some tidbit about how to make combustion more efficient and more powerful. But this was just a pretext. I think the truth was they came in to immerse themselves in the familiar, comforting, oily stink of a workshop. Just being there was a way for them to be near something bigger than themselves, to pay their respects to a body of knowledge and a way of being.

If you go visit any working shop you’ll likely find a massive catalogue of stuff and tools and information that is only truly accessible to the ones who dwell in it and shape the space. There’s a certain kind of intelligence, a tool knowledge, a practical comprehension of systems, the way they function and interact. Some of the smartest people out there are those whose hands get dirty while at work. You don’t even know how to properly respect it unless you know enough to know how much you don’t know. Bow to the grungy wizards, right?

Visual Shop Tour

And to be clear, I’m not (so to speak) tooting my own horn here. I’ve got a bit of baseline knowledge, I know how to use some tools and to put together a decent bike, but my skillset is very limited compared to any number of other shop people out there. Whenever I talk with one of my machinist friends, like Kristina, Roger, Oscar, or Sean C., it’s so clear I’m a hack. These people are brilliant, the breadth of their skills and knowledge base makes me feel like a toddler in a tool room.

Anyway, I was talking about Codger Visitations. I enjoyed watching these old guys chewing at their dentures as they ran their eyes over the bike wheels and partial frames hanging overhead. Craft is craft, it has a certain nobility to it whether these old guys cared for the final product or not.

Underneath, too, a part of me felt righteous about showing these old dudes the facts of a changing tide: Once upon a time there were muscle cars here, but now an environmentally friendly Mercedes mechanic and bicycle fab shop had taken over. To my thinking the world was moving in a better direction.

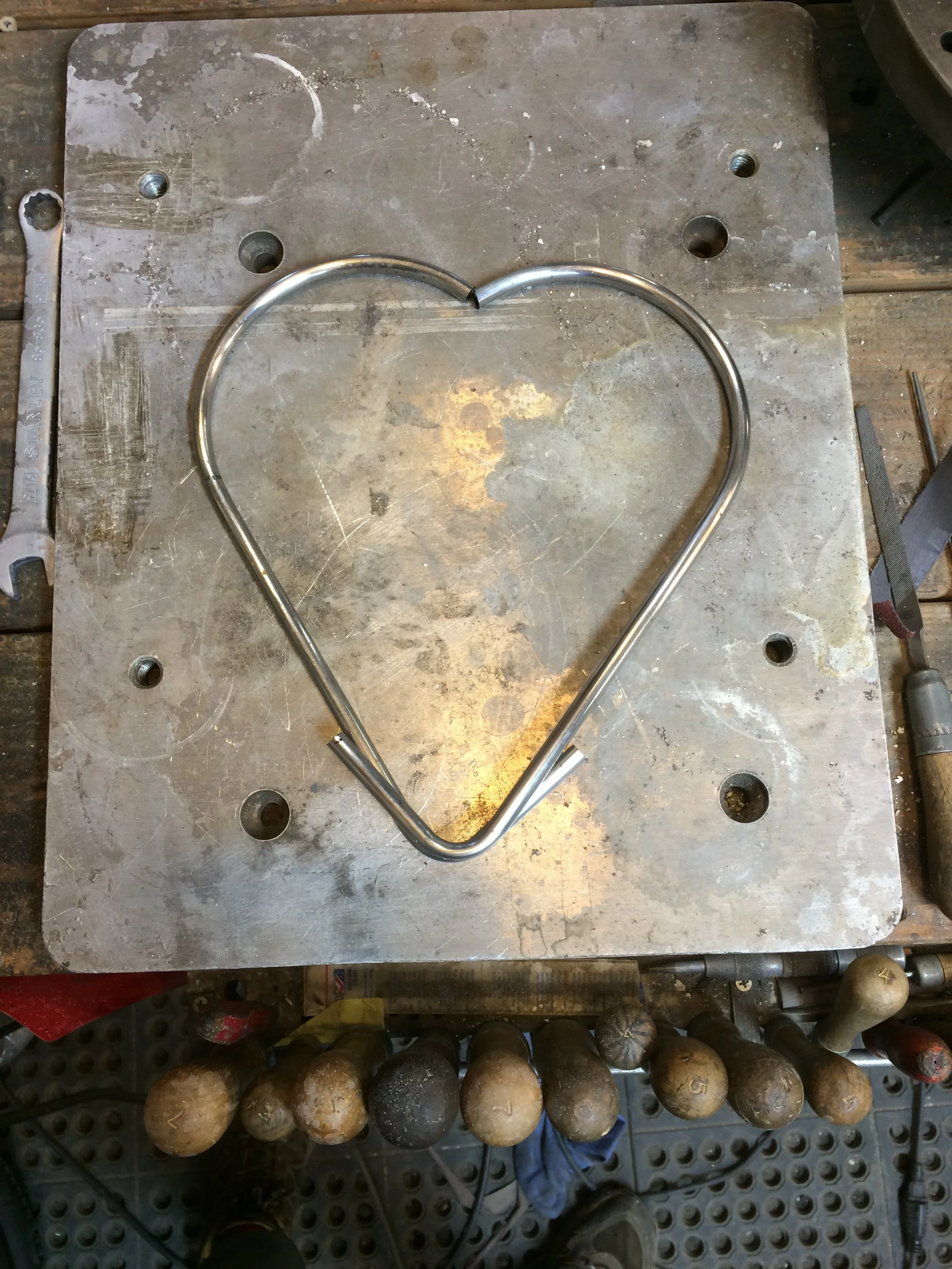

Put your heart into it

Bless them, though. You could still see the spark of a motor revving in their eyes. These codgers just hadn’t yet gotten the memo that this race was over.

________________________________________

Change happens.

Jay and I were shop mates for a few years until he bought a house and moved his mechanic business into his garage. That was a dozen or more years ago. Afterwards, the shop became fully bicycle-centric. Mitch of MAP Bicycles got his start here and worked a few years before moving on to Chico, CA., and after him Christopher Igleheart was here for a decade until he retired. Now I’m moving my business into my own garage workshop — no more landlords, hopefully ever.

To repeat — and to be clear — I’m not quitting the business, I’m just moving out of this space. Ahearne Cycles and Page Street cycles will be up and running again in the next couple of months, as soon as I get my new shop built out and ready.

I’m going to miss this space, and I’m going to miss the people around it, connected to it. My friends. So many folks have come through over the years. The memories are rich. But I’m ready for this change.

I wonder what’s coming next for the Page Street workshop. Once I’m gone will there be scrappy old bike heads popping in, chewing at their dentures as they scowl at some youngster trying to eek out a living, asking about that old Ahearne bike builder?

Who and what business will be here to greet them?

It’s a funny feeling watching my own history here at the shop, the many years’ worth of stories, about to become the relic. It’s already happening. The first layer of new dust is beginning settle over the old world, my world, and I’m not going to be around to disturb it or clean it up. That’ll be someone else’s job.

Transitions are weird because you can’t know what’s on the other side. You can do your best to set yourself up, but the only way to find out what’s coming is to close one door, turn around, open the next and walk right on into the light.

Onward

Here we go.

I’ll see y’all on the other side.