Thoughts and Updates

Made PDX

Made PDX happened toward the end of August. It was the first bike show I’d been to — most of us had been to — in a lot of years. By everyone’s reckoning, it was a success. I heard some bike news that this was the most attended handmade bike show in North America — ever! True or not, more than 5,000 attendees came through and the place was a-buzz with enthusiasm.

Another event:

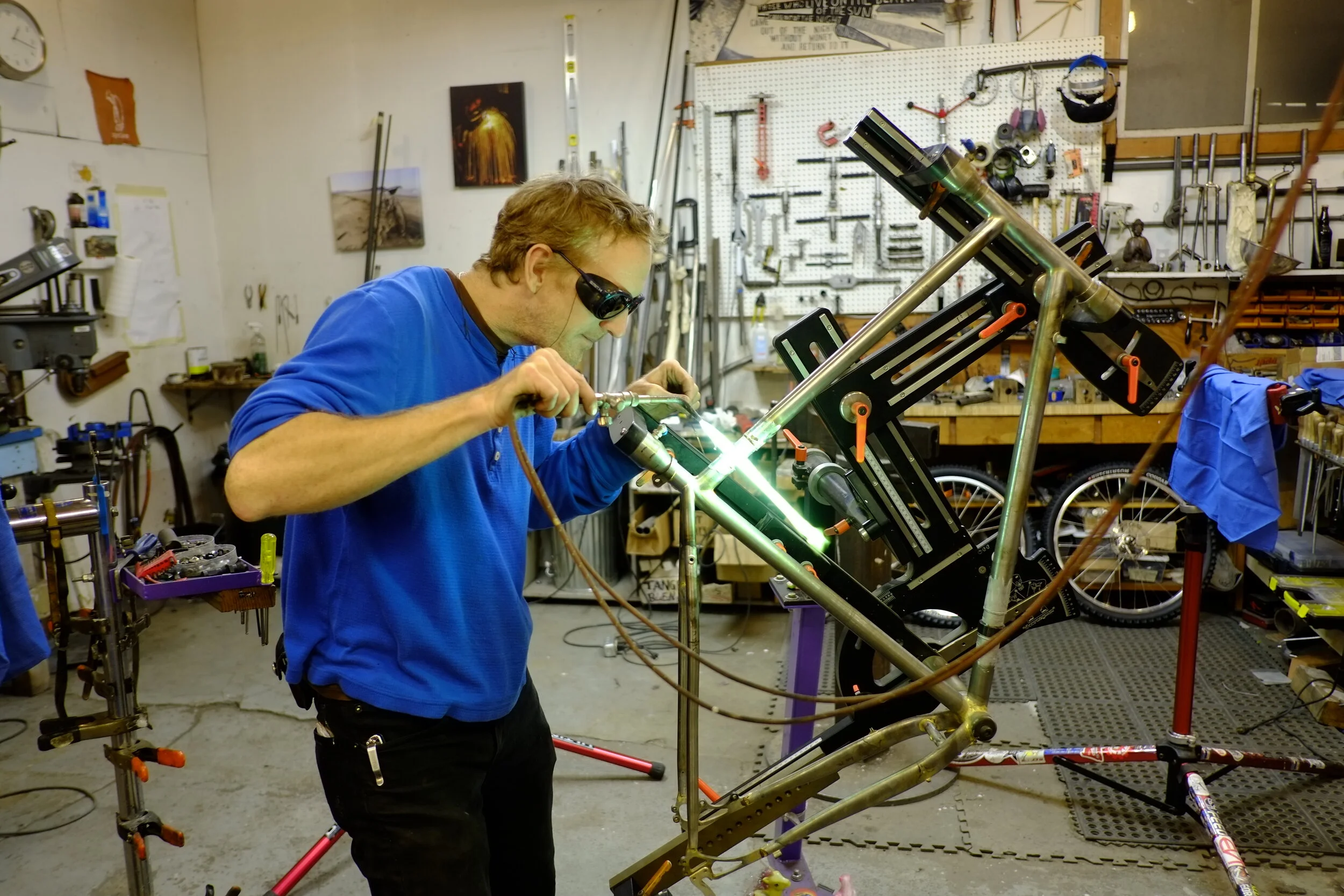

This year marks my twenty-year anniversary of making bicycle frames. I tried to pretend that Made PDX was partially a celebration of this, a giant gathering of new and old friends to acknowledge two decades of my practicing the craft of bike making.

Twenty years!

“Not dead yet!”

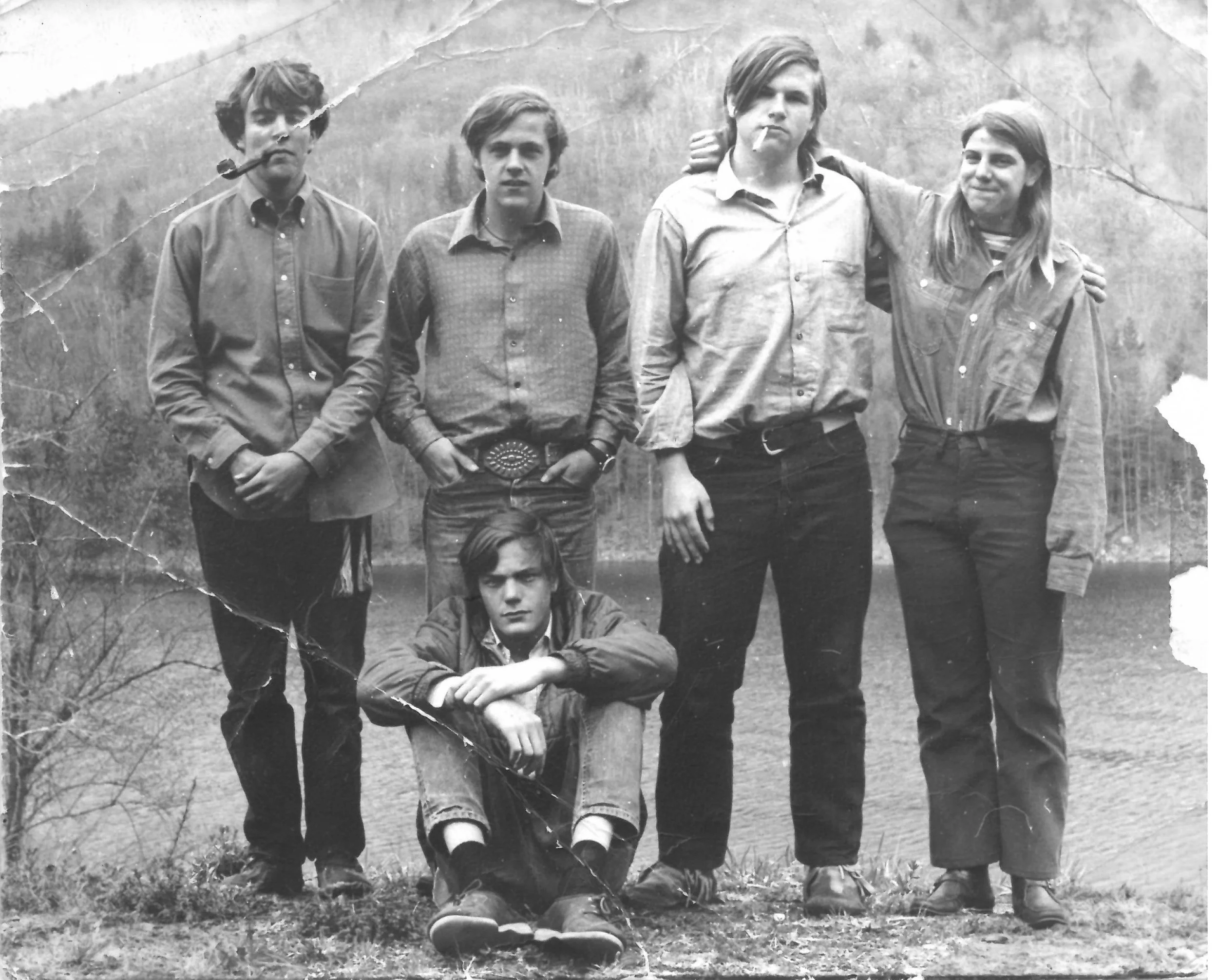

I think this almost qualifies me for being considered one of the old-timers. How did I even get here? So many bespoke frame makers have come and gone over the years, and at some point it comes down to who’s left standing. As my old shopmate liked to say, “Not dead yet!”

I’m not saying I’m better than anyone. I honestly don’t know if it’s a virtue of persistence that keeps me doing this, or if I have some sort of barrier to higher thinking, like a chronic mental deficiency. None of the is job easy, the struggles are real. Do it long enough and the struggles will change, but they never go away. One quality, perhaps more than all the others, that one must have to survive as a frame builder is mulishness. Being like a mule. Undying determination. Not considered the smartest creature, but tenacious to the end. Is that me, the ass?

Each person who made bikes and then stopped making bikes had their reasons.

Igleheart retired after like forty years of doing it, and moved with his wife to France.

Mitch lost all his equipment, not to mention his home, in the Paradise fire.

Bruce died.

Tim did well for himself for a number of years, but being a school teacher and receiving a steady paycheck, health insurance, and a decent retirement package was a much wiser choice, really a no-brainer.

Natalie became a mother of two, which is more than enough work to keep one busy.

Aaron realized he could make more money if he went back to being a graphic designer.

Sean needed to focus on being a dad and to free up space in his garage. And besides I don’t think he really liked dealing with customers.

Sacha’s mustache got in the way. The last anyone heard he used it to paddle out to sea and never came back.

Making things to make a living is hard work

Matt got into grad school and his partner Nate didn’t want to keep doing it solo.

Other people I’ve known started out just wanting to make some frames and were never really keen on the business side of things. And who can blame them? If you’ve got another job or another source of income, sure, OK, make bike frames as a hobby.

As one’s sole employment, though, it almost doesn’t make sense. The numbers hardly pencil out unless you arrange your whole life around it, and not everyone is willing to do that. I did it, I’ve done it, but I again refer you back to what I was saying earlier about the mule and dysfunction of the brain.

Just to acknowledge it, though: After twenty years I can still honestly say that I enjoy making bikes. I really do. I like designing something cool, letting my hands do what they know how to do. I like problem-solving and using a torch and files to construct something that I know is going to be good, functionally and aesthetically. I like working for myself, answering to no one except for my customers. I like taking an idea, building it into steel and then passing it along to its new owner. In a way it feels like I get to open a door for someone, invite them to come inside and join a banquet. Not in my honor, but in theirs. Of course I have to get paid, but in some ways it still feels like I’m giving a gift.

A new bicycle is like a promise. It goes out into the world, hopefully to be ridden a lot, to make new stories on the road — of travel, of speed, of fun and engagement. I get to make something that contributes to a person’s health and happiness, that’s kind to the environment. These are the things that fuel me, gratify me, and make me feel stoked. All this is its own sort of capital, impossible to measure in linear terms.

Anyway, off the soapbox, there are a couple of other things to note…

One, I wrote a book! Not that this is a recent development — I’ve been working on this thing for ages. But earlier this year I was accepted into a program to have high-caliber writers read what I’ve written and do a full manuscript review. It’s the next big step towards crafting something that will (hopefully, eventually) be put out into the world. You’ll hear more about this in the coming months.

New T-shirts!

Next thing: There’ll be t-shirts for sale on the Ahearne website soon. Commemorative and possibly historic designs, etc. Colors, sizes, options. I sold some at the show, they’re nice, you’ll like them. Thanks Brian, Maggie, and Mary Lou for pushing to make this happen!

And lastly (for now): If you hadn’t heard, Page Street Cycles is still a thing. It’s going through a transformation, and there is a website being flushed out as I write this.

At Made PDX I introduced the newest Page Street model, a mini velo travel bike called the Viajero (Spanish for “the traveler”). Prototypes have been up and running for a few months, the design is getting dialed in, costs determined. You can read a bit about it in The Radavist (scroll down through the other cool bikes to see it).

I’ll admit, the Viajero is one fun bicycle. The way it breaks down it will be an amazing bike for taking with you when you head off to far-away places. It’s not a folding bike for instant break-down. The goal is to have something that rides, handles, and feels like a “normal” bike and that easily packs down into a suitcase within airline regulations, or to fit in the trunk of a car. I picture it being for people who travel, a few days here, a week there, and want to take a bike with them that’s easy to manage. I’m building it so it’ll be stable enough to bike tour on if you wanted. Like, I could see doing a mixed train-and-trail tour across Europe on this bike. That’d be a riot.

I won’t go into it further just now. Suffice it to say I’m excited about this bike. I’ve been riding one for the past couple of months and it’s been a real treat. It’s zippy and quick handling, intuitive, and just a blast to ride. I love atypical bikes that serve a specific purpose and do it well. And these bikes rip. I’ve gotten quite a bit of interest already, and plan to start taking pre-orders as soon as the details are figured out.

If you’re interested in knowing more about the Viajero and staying in the loop as things progress you can email pagestreetcycles@gmail.com and ask to receive notifications. I’ll have a sign-up list soon, but for now this will get you started. I promise I won’t share your email with anyone, and I will only message you when there’s real news about the bike.

That’s it for the moment. Thank you for reading this, and cheers to everyone who made it to the Made PDX bike show. Especially Billy Souphorse — seeing the need and taking it on. Seriously, give you and your crew a pat on the back.

And, most importantly, thanks to everyone who’s supported me in what I do, and have done, for the past twenty years. What a ride!

Time to chill.

Or, as some hippy once said:

What a loooooong strange trip it’s been.